Design to Fabrication

Computational thinking to digital fabrication

Parametric design – also known as algorithmic thinking, computational design or associated design – is an approach that introduces a dynamic framework defined by specific variables in equation form. This allows the production of a series of iterations that respond to the same brief within the coherence of the given rationale.

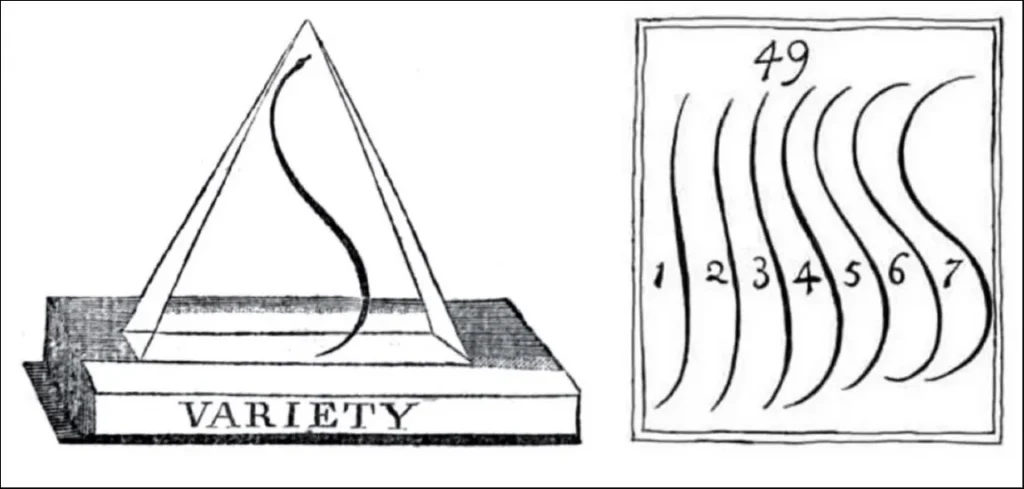

The result is what Gilles Deleuze would call “infinite representation,” different entities whose properties present the very same logic. For example, an object would have identical geometric relationships characterizing its shape. This idea aligns with Hogarth’s argument in The Analysis of Beauty, which asserts that among various curves, only a particular one strikes the ideal balance between excess and insufficiency.

Drawings from ‘The analysis of Beauty’ by William Hogarth (1753).

This design process was the very same that marked the invention of architectural design by Leon Battista Alberti. In his theory, architectural design is a set of spatial coordinates that can be adapted to different contexts. Any proposal he would draw on paper would be carefully parametrized to ensure that its materialization on site would be accurate to his design. Therefore, a building would be an identical copy of the architect’s design. This logic set architects up as authors, a novel concept in his time that bridges the gap between the technical vision and the object.

In a time where technological advancements allow for the recording, storage, processing, search and use of an unlimited amount of data almost instantly, architects are presented with the opportunity to inform their designs with a huge amount of information. The integration of 3D printing technologies in manufacturing architectural components unlocks the possibility of establishing a closer relationship between design and production. Architects’ proposals are no longer a mere modelization of data that need to be exported for an external interpretation, but compilations of dependencies in the form of parametric code. The identity of the object is consequently embedded in both the design and production processes seamlessly.

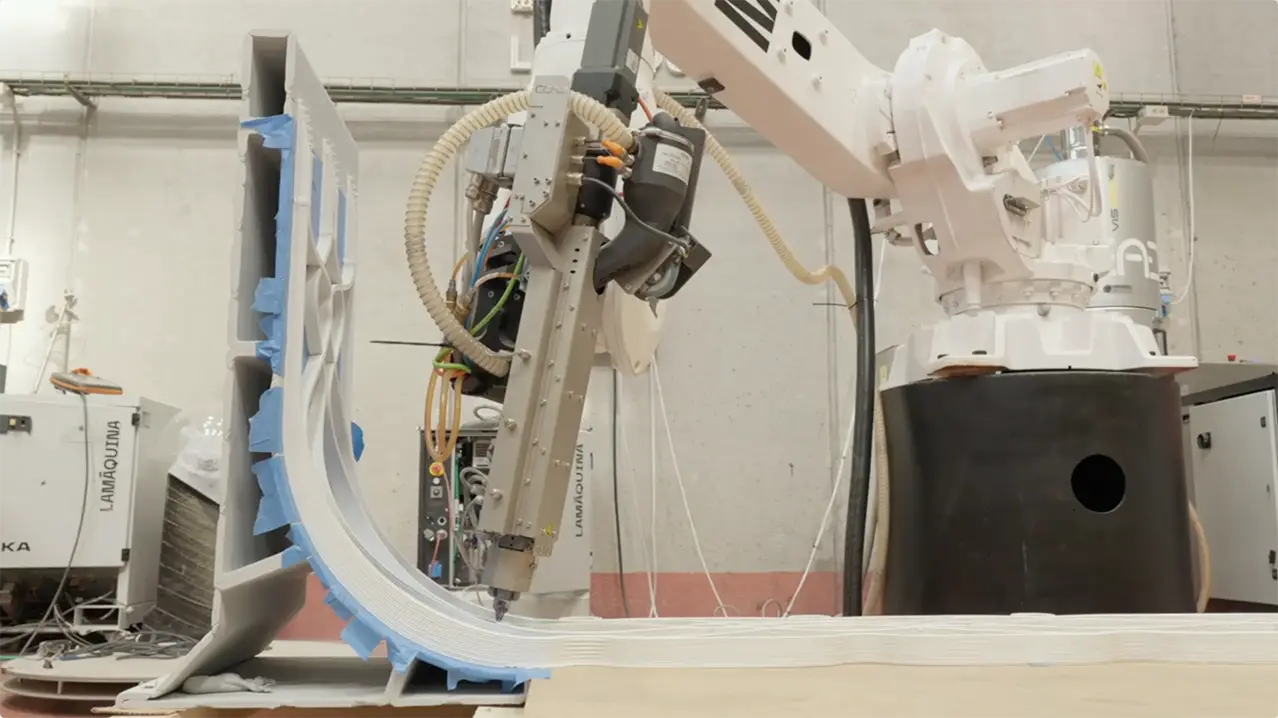

For the retail project for the womenswear brand Pinko at the Rome Fiumicino Airport, LAMÁQUINA explored the potential of 3D printing by pushing the limits of the capabilities of software and hardware. The design, drafted by External Reference Architects, aimed to redefine the retail experience while infusing the brand’s character. Echoing their iconic clothing patterns, the proposal introduced a skin that subtly morphs from straight lines to sinuous curves, adapting dynamically to meet all programmatic needs. Due to the constraints of working within airport facilities, the construction timeline was compressed to only three days. This limitation required a design that could be easily assembled with speed and precision. Therefore, the strategy consisted of a series of pieces based on a singular element that expands and contracts within a brief, achieving an accurate adaptation to its context and a precise coordination between the pieces. This approach takes up Deleuze’s concept that defines the difference as the “ultimate unity”. By parameterizing the logic of the piece, the differentiation between them constitutes a variable relation that maintains its belonging to the same chore. This nonstandard serialization allows the creation of a structure perceived as a whole with the adaptability of being constituted by different elements perfectly fitted in their position.

The use of non-conformal 3D printing processes broadens physical limitations to realize particular shapes. For this project, the challenge was overcome with a mold that enabled a customized spatial form. The pieces rise vertically from the ground and curve toward the ceiling creating an organic envelope that welcomes customers to the space. The geometries were produced using cellulose, a natural polymer obtained from renewable sources, which not only aligns with circularity principles but also meets with class BS1D0 fire regulation compliance. This project marked the first time such strict regulations were achieved in a 3D-printed store in an airport. All these technical requirements, together with the aesthetic qualities of the space, were ingrained in its coded definition, ensuring cohesion between the geometric form and its materialization through a single parametric code.

The building of a digital twin – a virtual replica that simulates the fabrication workflow – further enhanced this approach by enabling precise planning and optimization from the deposition of the material to the introduction of other structural elements. This has reduced the production time of all the pieces to as little as two weeks, optimizing the entire process from ideation to finished project. The ability to create tailored components with high precision in short production times is reshaping how spaces are conceptualized and constructed.

The relationship between creativity and technology has transformed architecture and design, especially in the retail sector, where value transmission and timing are key. Through a design-to-fabrication approach, brands can now partner with designers who innovate for sustainable spaces that offer a singular experience to enhance the in-store relationship with their customers. Thanks to its capability of reaching high levels of accuracy and bringing down production times, advanced 3D printing has become a game changer for retailers aiming to upgrade their spaces without compromising on environmental impact.